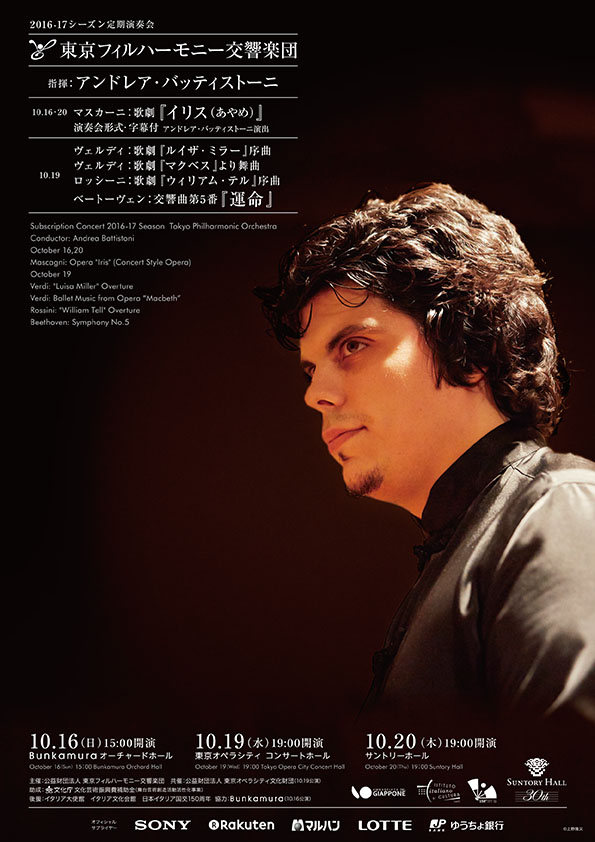

Andrea Battistoni, Chief Conductor

It is undeniable that Pietro Mascagni is one of those composers remembered by the public for a single work, specifically Cavalleria Rusticana (1890), which contributed to ignite his international career, but whose extraordinary success overshadowed his lasting artistic development in the following years.

Mascagni has been a famous and celebrated composer in his life, but a certain intellectual snobbery typical of musical critics has never frown upon his legacy, and has contributed to the unrelenting disappearance from the scenes of all his mature operatic works. On the other hand the popular success has instead made the Sicilian opera that started verismo among the most staged in the world, giving to the music lovers an incomplete picture of this great Italian musician.

Isis is certainly the work that more than any other deserves to get out of the limbo in which it has been relegated. So many are the reasons of interest that encourage to approach and be captivated by its originality.

Pietro mascagni

Intuition has always been one of Mascagni’s distinctive features: he was able to intercept the trends and the international fashions well before they would become followed in Italy and spread as social phenomena. In fact, Cavalleria gave birth to Opera Verista, a very fortunate sub-genre; Amico Fritz (1891) did it to the bourgeois and idyllic Opera Biedermeier, much before this style would appear in Italy; Parisina (1913) interpreted the D’Annunzio aestheticism with vigorous dramatic force; Isabeau (1911) the revival of medieval tales.

Iris certainly took its moves from the Oriental and Japanese fashion that in the 1870s had invaded the French capital, the World Expo, the influential salons, and then spread to Europe with a very singular image of Japan.

The Japanese Women In

The Late Paris International Exhibition

The ukiyo-e, with their imaginary atmospheres, the exotic subjects, the unusual costumes for Europeans, the fairy-tale, erotic, fantastic atmospheres contributed no little to get Japan into the imagination of writers and painters in Europe, and they gained a new life flowing into the collective imagination, already blurred by the nocturnal and seducing images of Symbolism.

Therefore here we have the first Italian-Japanese opera: the comparison with Madame Butterfly (1904) which would come out 5 years later is obvious.

Anyway the issue is ill posed; one could not compare more different operas.

Giacomo Puccini

Puccini, from the debut with Manon (1893) to the Trittico (1918), remained essentially true to himself and his own poetic, without any risky experimentation: his taste for dramatic symbolism and multifaceted characters carefully described in music would remain unchanged for years. It is necessary to wait for Turandot (1924) to see a blooming opera, unfortunately unfinished, spreading from the decadent roots of myth and the extravaganza of symbolism.

Mascagni goes against the grain of the Italian scene of the time: instead of pleasing the public with stories whose protagonists are easy to identify with, using an almost cinematic taste; Mascagni imposes an anti-theatrical tale, a plot without dramatic twists, a star that is lost and elusive instead of being a strong willed heroin, and a quite unusual setting for an opera, the mysterious land of Japan.

And yet , these elements have stimulated Mascagni creativity, pushing him to the bold and original solutions. We are far from Puccini’s attempt to recreate a local tint through the use of whole-tone or pentatonic scales, the quotation of authentically Japanese tunes and to draw a realistic - if not faithful - portrait of Japanese customs.

Mascagni makes Japan a land of dream, where Symbolism reigns; Hokusai’s prints come to life in front of our eyes, although governed by the visionary power of a European, more spontaneous than learned, that redraws the scenes according to his taste and fantasy.

The great orchestra speaks the language of Wagner and the late romantic opera, with fascinating timbres and a refined technique, owing to the French style and enriched, here and there, by the sound of the exotic instruments that Mascagni had listened to at the private collection of a scholar in Firenze.

Tuned gongs

Tuned gongs, folk Japanese drums and even a shamisen make their first appearance in a European theater (Puccini will be amazed and will remember them when composing Butterfly and Turandot) contributing to the general sense of strangeness and uniqueness of this opera.

The characters themselves appear as shadows, masks, ghosts, personifications of human subconscious: the Blind, Kyoto and Osaka are just puppets that Mascagni, as a Bunraku master, handles as symbols of greedy passions, selfishness and evil.

Iris stands as the opera unwilling heroin, but without the feral femininity of Tosca or Santuzza, without the tragic pathos of Cio-cio-san or Isabeau; Iris is quintessentially naive and delicate, akin to the beauty that Mascagni had probably seen in the screens and the stylish designs.

And finally, the most exuberant and over-the-top side of Mascagni’s liveliness contributes to make this controversial masterpiece even more multifaceted: the composer shows no reservations in making the Jor serenade a sort of Italian ditty between Il Trovatore and a Neapolitan song, and in transforming the Octopus Aria in a great primadonna verismo piece, drenched in torrid eroticism, so exciting and yet somehow unexpected and alien to the character.

An unbalanced and forgettable opera, then?

Quite the contrary: its apparent flaws are part of the irresistible charm of Mascagni’s writing, upon which we could fasten a new label, the one of Eclecticism, since each element - be it popular, romantic, symbolic or catchy - is simply one possible piece of a broad mosaic, filled with bright, vivid colors!

Rediscovering it gives us the chance to know the real masterpiece of Mascagni.

Lovers of refined aesthetic balance will grimace here and there, those who expect a second Butterfly will be disappointed; all the others will find themselves gradually carried away by the incredible talent of a too often overlooked composer, who deserves now more than ever a full rediscovery in the name of an unstoppable, irresistible fantasy.

Buy your ticket online

The 150th Anniversary of Diplomatic Relations between Italy and Japan

Subscription Concerts in October

The 886th Subscription Concert in Bunkamura

Oct 16, 2016, Sun 15:00 start

Bunkamura Orchard Hall

The 887th Subscription Concert in Suntory Hall

Oct 20, 2016, Thu 19:00 start

Suntory Hall (Main Hall)

Andrea Battistoni, conductor / stage direction

Rachele Stanisci, Iris (soprano)

Francesco Anile, Osaka (tenor)

New National Theatre Chorus, chorus

Mascagni: Opera "Iris" (concert style opera)

![BUY TPO TICKETS [03-5353-9522] Business hours: 10:00~18:00 Regular holiday: Sat・Sun・Holiday](../../img/common_en/bnr_inquiry2.png)